Most evenings before bed, I’ve taken to scrolling through Instagram in a bid to decompress - which is my favourite new way to describe ‘winding down’.

In amongst clips of donkeys being adorable, dogs having coherent conversations with their owners, and ads for miracle neck creams, are videos of comedians from yesteryear telling jokes. They aren’t regaling shared truths from the past, neither are they satirically pulling politicians to threads, instead they are telling actual jokes, in which words are used within a defined narrative structure, usually in the form of a story ending in a punchline, often resulting in a laugh.

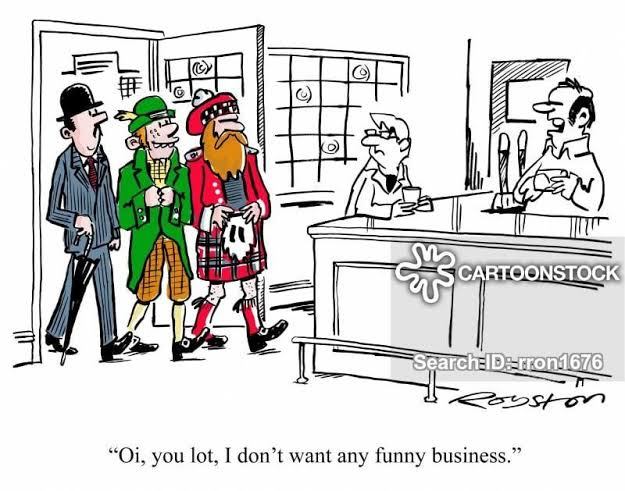

I’m not saying that they all stand the test of time. Racist/sexist jokes have quite rightly been assigned to the bin. But I for one miss the era of the storyteller, the days when an Englishman, Irishman, and a Scotsman walked into a bar. As a plastic paddy, I can attest that my family bore no grudge to the fact that these jokes quite frequently reinforced national stereotypes. Far from being offended, the Irish often embraced their role as the perennial underdog with good humour and resilience, turning stereotypes into sources of strength and unity.

It certainly helped that they were a nation of masterful storytellers, and during this time, one comedian stood head and shoulders above the rest - Dave Allen - an Irishman renowned for his sharp observational wit, who’s only props were a stool, a glass of whisky, and a wry smile. Allen often courting controversy by exposing political hypocrisy and mocking religious authority, it’s no surprise that he had once worked as a journalist; his delivery was razor-sharp, and his timing impeccable.

Back then we were rather spoilt for choice, as comedy was the mainstay of the television schedule, but as the saying goes, the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.1 Despite since facing criticism for his offensive material, it was a time when Bernard Manning pushed boundaries and remained a popular comic on the club circuit, drawing crowds back time and again.

In the pre-television era, mastery of timing and narrative remained paramount, especially in the realm of radio comedy, where visual aids were absent. Successful comedians relied solely on the quality of their writing and the delivery of their jokes to captivate audiences. It is notable then, that those who made the transition from radio to television, men such as Peter Cook, Barry Cryer, Ronnie Barker, and Bob Monkhouse, are still remembered today as exceptional comedic raconteurs.

Despite the era's rich comedic talent, it’s no surprise that female comedians were largely absent. While there were actresses who were successful, stand-up comedy remained predominantly male. Although the feminist movement made significant progress in British politics post 1970’s, women continued to face considerable discrimination within the industry and it wasn’t until the emergence of alternative comedy, did they get a foot in the door.

Defined by its opposition to what was considered the antiquated humour of working men’s clubs, the genre is commonly associated with the opening of the Comedy Store London, in 1979, and spawned a movement which saw a departure from the traditional structure of sequential jokes with punchlines. Instead, it delved into various types of material, frequently straying toward the surreal and anarchic. Left wing in its approach, and anti-establishment, the comedian Arthur Smith called it, “Comedy’s version of punk.”2

But while alternative comedy emerged as a significant force at the time, it wasn't altogether new. Monty Python’s anarchic humour of the early 1970’s is widely acknowledged to have been influenced by The Goons. In addition, folk performers like Jasper Carrot and Billy Connolly were already exploring alternative comedic styles before the term gained popularity. Even Dave Allen was presenting observational narratives infused with satire before the term 'alternative comedy' was coined. These pioneers mastered the art of delaying the punchline without losing the crowd, skilfully venturing into various tangents along the way. Alternative comedians such as Ben Elton and Harry Enfield did perform solo, but unlike traditional stand-up, their brand of humour was mostly character-driven, their vehicles, sketches.

The alternative comedian's aim was widely interpreted as striving to establish a more abstract connection with their audience, with a mission to eradicate discriminatory humour. So out went the mother-in-law jokes, and as comedy evolved, so did audience preferences. But while laughter once bridged generational gaps, in my house we began to witness a divergence in comedic tastes. It's too simplistic to categorise this divide solely upon age or comedic style. For instance, my parents enjoyed shows such as Not the 9 O Clock News, and I never missed an episode of Russ Abbott’s Funhouse (ahem). Nonetheless, a shift was palpable, as comedians increasingly challenged authority and encouraged their audience to do the same. Minorities were no longer the butt of the jokes, but everyone else was fair game.

We now live in a time of the ‘woke’ – derided by some as a movement which has resulted in a culture which cancels anything remotely amusing, defended by others who believe it to be a force for good, allowing for a sensitive approach - but back in the 1980’s, the gloves were well and truly off.

So when a puppet show arrived on the scene which was not only visually spectacular, but extremely funny, it felt like the final nail in the coffin for old school comedy. In Spitting Image, the observations were personal, the jokes cutting, and the humour satirical. However, John Lloyd, the producer on the show at the time, has since refuted that tag, arguing that “Spitting Image was there for the people who worked hard all week and had to get up at six o’clock on a Monday morning, who wanted a bit of a laugh at people who were richer and, in their eyes, didn’t have to work as hard as they did.”3

Indeed, the working classes not only got the joke but needed little encouragement to join in the mocking of authority. I recall my father would laugh hearty when the Queen Mother was depicted as gin soaked lush and equally so when Margaret Thatcher’s puppet made goo goo eyes at Ronnie Regan. As anyone with even a basic understanding of Anglo-Irish relations would know, my father was far from being a Royalist, although he did harbour a reluctant admiration for Maggie.

But at the end of the day, even when its goals were intentional, alternative comedy was ultimately unreliable as a cultural weapon, largely because a show like Spitting Image was popular even among the people who were often made fun of, those on the political right.

This acceptance and enjoyment of the parody by its subjects reflect a historical pattern where comedy and satire significantly influence and are often embraced by those being mocked. Just as my Irish family would laugh at the Paddy jokes, these subjects were, and I’d argue still are, able to take critical portrayals in their stride, perhaps even finding value or humour in them, which is consistent with how comedy has traditionally impacted people and society throughout history.

Alternative comedy undeniably created a media landscape that reflected the values and perspectives of the same demographic of people who continue to shape cultural and political narratives now. Writers, producers, and TV executives, many of whom derided the working classes for finding Jim Davidson funny, simultaneously encouraged them to laugh at a depiction of Labour MP Roy Hattersley’s puppet covering everyone in spit, as a result of his real-life lisp.

In fact, Ivor Dembina goes one step further, writing for Chortle in 2016, he believes “Alternative comedy was driven by a hatred for the working class more than genuinely progressive attitudes.” Speaking in a session on taste and decency at the Comedy On Stage And Page at the University of Kent in Canterbury, Dembina argued that “Taste is economically determined, rather than being driven by 'moral, social or political' factors.” He goes on to conclude, “…And now the prejudices of the middle classes determine what is 'acceptable' in stand-up.”4

Subsequently, much of what had once been “alternative” has incorporated into the capitalist cultural mainstream, almost entirely without its political baggage. The material has ultimately became populist and classless, establishing a new style of observational and responsive humour. This approach remains dominant today, with comedians such as Peter Kay and Mickey Flanagan regularly selling out arenas.

In an observational comedy act, the comedian makes an observation about something which is common enough to be familiar to their audience, but not commonly discussed.

But what of the storyteller and the subject? The gentle style of Alan Bennett and the genius of Victoria Wood? They spun tales and told jokes that made us eagerly anticipate the punchline, confident it would be worth the wait. In today's era of immediacy, our collective shared experience has shifted just as formats change—fracturing the audience with multi-platform viewing and immediate gratification through bitesize content and memes.

Coupled with the fact that we live in an era where comedy intersects with social consciousness. The role of comedians has expanded beyond mere entertainment. They are now commentators and influencers, shaping cultural narratives and societal norms. This evolution, driven by transparency and connectivity through the internet, has made comedy more narrative-driven but has also constrained comedic freedom, as audiences become more and more prescriptive about what is acceptable to laugh at.

As we head to the future, what will the landscape look like in ten or twenty years time?

Jordan Brookes, who won the 2019 Edinburgh Comedy award, suggests that audiences appreciate novelty and enjoy witnessing unconventional performances that deviate from everyday norms.

“If you want to do something different, just do something different. For me, the fun challenge is: how do I get as many people as possible on board with the weirdest thing?”5

But in their quest to be the comedian who wears the wackiest tie, do they sacrifice the essence of what makes something truly funny? In striving for uniqueness, there's a danger of overshadowing the humour itself, potentially eliminating the genuine laughter that connects with audiences.

The way I see it, comedians need to look outwards, not inwards, in striking a delicate balance between the need for sensitivity and the fundamental essence of humour as a vehicle for unrestricted expression. It's a challenge that raises profound questions about the very nature of comedy and its place in our evolving society.

Thank you for reading my work, I’m truly grateful for every like, comment and share! Pigeon Post remains free, but if you fancy sparing a few quid for this literate street urchin, please press on the button below, which allows you to buy me a coffee, as way of appreciation. 😘

Wrote L.P. Harvey in his 1953 novel, The Go-Between

https://www.chortle.co.uk/features/2010/05/13/10989/this_was_comedys_version_of_punk

https://www.nallon.com/?p=130

https://www.chortle.co.uk/news/2016/01/14/23954/alternative_comedy_was_driven_by_hatred_of_the_working_class

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2022/jun/29/beyond-the-comic-strip-what-does-alternative-comedy-mean-in-2022

I enjoyed this sensible deconstruction, and was very interested in Dembina's take on alternative comedy. I was a fan of the movement but it's undeniable that it was the start of very self-conscious virtue signalling which has now become cancellation.

Thanks Sharon, smashing piece.

I laughed all the way through reading this, but I need to come back and finish it because it’s so late at night.

I am so happy I found you. The drunk and the pigeon nearly had me pee my pants.

Thank you - you’re good !!!