As the lights dim and the opening titles roll, the unmistakable sound of alternating notes on a tuba - E-F-E-F - begin softly, slowly, before rapidly gaining momentum. The music then shifts, replaced by the gentle sound of a harmonica. The tension fades, and what seemed like looming danger softens into a moment of carefree, almost whimsical calm. Look! Drunk hippies on the beach having a singsong. Nothing to worry about after all. What’s that, Chrissie? You’re going for a night-time swim? Great idea, have fun!

This is no ordinary screening of the 1975 classic Jaws. I’m lucky enough to be sitting in the Sydney Opera House, on the film’s 50th anniversary, watching The Metropolitan Orchestra, conducted by Sarah-Grace Williams, perform the entire score in sync with “one of the greatest motion pictures of all time.”

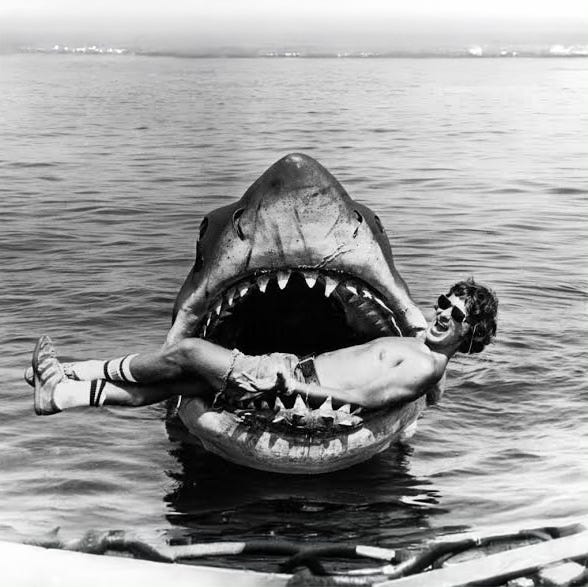

I’m not alone in my, frankly, obsessive love of Jaws - or as the French promoters called it, The Teeth of the Sea. But for those in the know, he's simply Bruce - one of three mechanical great whites built for the film, all of which proved notoriously unreliable. The ensuing struggles with production and budget forced Spielberg to rethink his approach, relying less on the shark and more on shadows, floating barrels, and, of course, John Williams’ haunting score to create tension. How fortuitous.

Recognised as one of the most influential soundtracks in cinematic history, Williams’ use of the leitmotif technique - where a recurring musical phrase signals the presence of the shark - heightened fear and anticipation, proving that what we hear can be just as terrifying as what we see, turning music into a character of its own.

While this approach became a landmark in film scoring, influencing how tension and terror are conveyed, it draws on a technique dating back to the Silent Film Era (1890s–1920s), when live orchestras or pianists accompanied films, using music to enhance mood (e.g., frantic piano for chases, ominous notes for danger). Later, Hitchcock, often working with composer Bernard Herrmann, revolutionised how sound and silence manipulated audiences - Psycho being the key example, with Herrmann’s now-infamous shrieking violins in the shower scene.

However, unlike Psycho, where music amplified violence during an attack, Jaws signalled danger in advance, instilling fear before the threat even emerged. In fact it’s 81 minutes into the film before the shark makes a full appearance.

For my generation (Gen X), the blockbuster movie became a defining part of our childhood pop culture. At the Opera House, the audience spans a variety of age groups. Parents have brought their teenagers, many proudly sporting Jaws t-shirts. Regardless of age, one thing unites us all: the orchestra, who, as a collective, are electric in their performance of a score which earned Williams an Academy Award. We are encouraged to cheer and clap - which we do, wholeheartedly. The anticipation is palpable as Chief Brody prepares to deliver that immortal (and improvised) line:

“We’re gonna need a bigger boat!”

The roar of the crowd itself is a jump scare, and I find myself unexpectedly emotional. The film is filled with quotes we all recognise, we’ve heard these lines countless times, at different points in our lives, but the shared experience of hearing them in the Opera House as one unified audience reminds me of a period before the fragmented world of the internet and streaming. It’s a moment that matters, a collective memory we tap into, acknowledging the power of shared cultural experiences.

Jaws left a mark on many when it hit cinemas in 1975. Viewers screamed, some vomited, and others fled in terror, unprepared for its sheer intensity. The film's portrayal of shark attacks reportedly led to an initial decline in seaside activities, but speaking from personal experience, the thought of a great white swimming among the verruca plasters in our municipal pool in South-East London didn’t stop me from getting in - the fear of water did. Or rather, the fear of drowning (to paraphrase Brody).

My favourite bits? Too many to list, but special mention goes to the 4-second zoom-in shot of Brody watching little Alex Kitner1 get eaten in front of the whole beach. Goddammit - I felt for him in that moment. He knew, we all knew what was coming.

What I hadn’t considered before now, was how Williams’ score divides the film into two distinct tonal identities. The first half delves deep into horror, with ominous low-string cues and the relentless dominance of the shark theme. In contrast, the second half embraces a more adventurous, swashbuckling tone, highlighted by the sweeping 'Orca Theme' as the heroic trio sets sail.

I can only imagine that when cinema-goers first watched Jaws, this shift in music must have sparked a fleeting sense of excitement and purpose, as Quint, Brody, and Hooper embarked on their fateful hunt for the killer shark. No spoilers here… But let’s just say the mission didn’t quite go to plan...

Special mention also goes to the gallows humour in the title of this piece of music, played as holidaymakers flock to Amity Island, blissfully unaware of the nightmare awaiting them - ‘Promenade (Tourists on the Menu).’

As the film reaches its dramatic conclusion and the closing titles roll, the crowd in the Opera House erupts in thunderous applause. Then, as an unexpected encore, the orchestra launches into the iconic main theme once more - a relentless, pulsating rhythm that reverberates through the building. The synchronised motion of the violin bows, moving back and forth in perfect unison, is as mesmerising to watch as it is to hear. This is more than just music; it is a primal force, stirring something deep within us - our collective heartbeat racing in time with each pounding note.

We leave the Opera House exhilarated. The cultural impact of the Jaws score is undeniable, a testament to the power of music in storytelling. And for me, the film remains endlessly re-watchable - now with a newfound appreciation for both its sound and its spectacle.

Thanks for the positive feedback on my previous piece - The Final Countdown - a humorous take on planning your own funeral. I’m so glad it struck a chord.

If you enjoyed this Jaws post 🦈 please ‘like’ by clicking the heart button below ❤️ - also feel free to comment and share. You’ll be helping others find me on this Sub we call Stack…x

https://x.com/thedailyjaws/status/1500603794119446537

Really enjoyed this read Sharon. It’s always fascinating to find out what happens in the moments when things go wrong and the results are spectacularly successful. If the Shark animatronics had worked, would the film makers have to had leant so heavily on John Williams? Would the film have been as good? Would it have been as frightening?

What a delightful experience! Jaws is one of my favourite movies. Despite all the problems with the shark it is a gem, with brilliant performances and editing. I think it's one of Williams' best scores, even though Spielberg thought he was joking when he first played it to him on the piano. It must have been great to hear it at the Sydney Opera House. I did hear it performed live once and it was lovely to hear a score you know well performed by a live orchestra.

As you say, so many memorable scenes in this film. In an appreciation I wrote a couple of years ago I mentioned the scene at the table where Brody's little son is mimicking him while Ellen looks on. Heaven! (Oh, and the scene where Brody, Quint and Hooper get drunk.) I'll shut up now. 😆